|

OGRE 14.5

Object-Oriented Graphics Rendering Engine

|

|

OGRE 14.5

Object-Oriented Graphics Rendering Engine

|

If we have a collection of entities in our scene that will not be moved, then Ogre can perform an optimization by rendering them in "batches". Modern GPUs are designed to render an enormous amount of triangles at once. We are able to take advantage of this through the batching techniques used by a Ogre::StaticGeometry object. Static geometry is a bit of a misnomer in this case, because we can use some tricks to accomplish things like grass waving in the wind, but the general idea is that this is an object that will not be manipulated a great deal. Good examples include rocks, trees, and buildings.

The full source for this tutorial can be found in samples directory Samples/Simple/include/Grass.h.

The first thing we will do is create the grass mesh we will be rendering. We will use a pattern you've probably seen to create the illusion of grass. We will render three square quads that have a grass texture applied to them. We will create one, then place another rotated 60 degrees, and then place a third rotated 120 degrees. This will create a simple illusion of 3D grass.

The first step will be to define some variables. We will define the width and height of our quad, then we will initialize a vector that will be used to define the four corners of our quad. We will again be using quaternions to handle rotations. Our plan is to use the vector to represent the orientation of the base of our quad.

This should look somewhat familiar. We have created a quaternion that rotates by multiples of 60 degree around the y-axis.

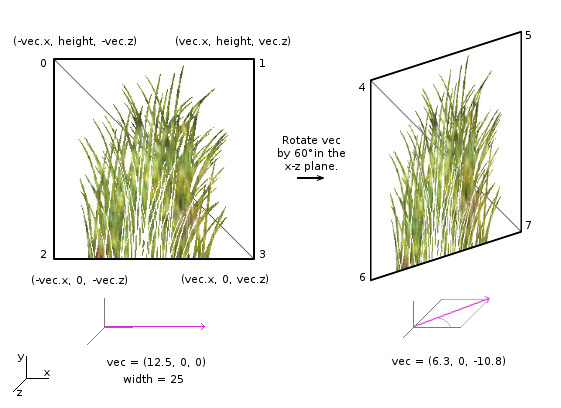

The vector we are using starts out pointing down the x-axis with a length that is half the width of our quad. This may be a little hard to visualize. Here is a picture to help:

Remember that x and z are in the plane of the floor. So our vector keeps track of where the foundation of our quad is, we build everything from that.

We will now begin defining our manual object. We set the render operation to be OT_TRIANGLE_LIST. This means that after we define our vertices with the position method, we then have to let Ogre know how to set up the index buffer by giving it a list of triangles made from the vertices.

For each quad we are going to define four vertices representing the corners. We will also specify a texture coordinates. These are normalized coordinates that tell Ogre how to map the texture on to our mesh. In our case, these coordinates are very simple since we are creating a solid square.

We've also labeled the four corners with the order they were created to help with creating the triangles. The count starts with the 0th corner.

To ensure that both triangles face the same direction, we need to provide the points in counter-clockwise order. The triangle method does not directly take positions, instead it takes three numbers that represent the order in which the points were created. This is why we labeled the four corners in our image.

First, ignore the offset value and look at the numbers we are adding. They match the numbers we assigned in the image. The first triangle connects the 0th, 3rd, and 1st corners. The second triangle connects the 0th, 2nd, and 3rd corners. You can look at the image to see these are in counter-clockwise order. The purpose of the offset is because we are creating three different quads, but they are all going to be a part of one manual object. So the second quad's corners will be numbered 4, 5, 6, 7. Adding the offset accounts for this.

After we've created all three quads, the loop finishes and we call end to finalize the object.

The last line converts our manual object into an actual mesh. Meshes require less storage compared to directly using the manual object for rendering.

We are now finished creating the grass mesh. If you create a complex mesh, then you may save it to a file instead of rebuilding the mesh each time. To do this, you would save the mesh pointer that is returned by convertToMesh. Then you would use a mesh serializer to export the mesh to a file.

Here is an example. Do not add this code to our current project.

Now we get to the creation of our static geometry. The first thing we do is create an entity from the grass mesh we constructed, then we ask the scene manager to give us a pointer to a new StaticGeometry object.

Here, RegionDimensions refer to the physical size of one batch. All grass patches located within the region will be treated as one. Patches outside the region will be in a separate batch. This allows you to trade culling for batching effectiveness.

Now we will prepare the actual build. We are going to loop through points on the floor of our region and place a grass patch with a random offset at each point.

We've partitioned the floor of our region into enough sections to fit all of our grass patches. The first thing we do is calculate an offset that will be used to randomly nudge each grass patch. This will help it look a little more natural. We use this offset to define a position vector for our object. To do this, we use the Ogre::Math::RangeRandom. We then use the same method to create a randomized scale vector to add some more variety to our grass. Our three quads were already rotated 60 degrees from each other, but now we are randomly rotating the entire grass patch as a whole. Always remember to play around with numbers like these to create surprising effects in your scene. Some great game mechanics have been discovered by doing exactly this.

The last thing we do is add a new grass entity to our scene using all of the information we've just set up. We then call the build method to construct our StaticGeometry object.

addSceneNode, be sure to remove the scene node from its previous parent. If you do not, Ogre will render them both.Once you have created a StaticGeometry object, you are not supposed to do much more with it. After all, that's the entire point behind static geometry - it's supposed to be static. As mentioned before, you can use certain tricks to do things like grass waving in the wind. If you are interested in how to do this, then take a look at the Examples/GrassBladesWaver material, which adds wave-like behavior to our grass meshes through a vertex-shader.

This is just the beginning of the batching technique. StaticGeometry objects are useful for grouping together many things that will not move. But if you're trying to create something more massive, like a forest or a large terrain covered in grass, then you should look into more advanced batching techniques. A good place to start is the PagedGeometry Engine. It works similar to StaticGeometry, but extends it with paging and automatic Impostor generation for LOD.

If you actually need your Entities to move in space or if each entity consists of many vertices, rather take a look at Ogre::SceneManager::createInstanceManager.