|

OGRE 2.1

Object-Oriented Graphics Rendering Engine

|

|

OGRE 2.1

Object-Oriented Graphics Rendering Engine

|

Attention!

This section was writen for Ogre 2.0 rather 2.1; it relies on legacy code. On Ogre 2.1; this section has become almost irrelevant as 2.1 can auto instance meshes automatically; and apply instancing even if the meshes are using different materials. The InstanceManager can only beat the Hlms if you have a very, very large number of instances (>50k objects) with the same mesh and same material, which isn't very common. If you're working on Ogre 2.1; you can skip this section.

Instancing is a rendering technique to draw multiple instances of the same mesh using just one render call. There are two kinds of instancing:

Hardware techniques are almost always superior to Software techniques, but Software are more compatible, where as Hardware techniques require D3D9 or GL3, and is not supported in GLES2

All instancing techniques require shaders. It is not possible to use instancing with FFP (Fixed Function Pipeline)

A common question is why should I use instancing. The big reason is performance. There can be 10x improvements or more when used correctly. Here's a guide on when you should use instancing:

If these three requirements are all met in your game, chances are instancing is for you. There will be minimal gains when using instancing on an Entity that repeats very little, or if each instance actually has a different material, or it could run even slower if the Entity never repeats.

If your game is not CPU bottleneck'ed (i.e. it's GPU bottleneck'ed) then instancing won't make a noticeable difference.

As explained in the previous section, instancing groups all instances into one draw call. However this is half the truth. Instancing actually groups a certain number of instances into a batch. One batch = One draw call.

If the technique is using 80 instances per batch; then rendering 160 instances is going to need 2 draw calls (two batches); if there are 180 instances, 3 draw calls will be needed (3 batches).

What is a good value for instances-per-batch setting? That depends on a lot of factors, which you will have to profile. Normally, increasing the number should improve performance because the system is most likely CPU bottleneck. However, past certain number, certain trade offs begin to show up:

The actual value will depend a lot on the application and whether all instances are often on screen or frustum culled and whether the total number of instances can be known at production time (i.e. environment props). Normally numbers between 80 and 500 work best, but there have been cases where big values like 5.000 actually improved performance.

Ogre supports 4 different instancing techniques. Unfortunately, each of them requires a different vertex shader, since their approaches are different. Also their compatibility and performance varies.

This is the most compatible technique. It is a Software Instancing technique. World matrices are passed through constant registers, and thus the maximum number of instances per batch is 80; which quickly goes down if the object is skeletally animated. This technique does not play very well with skeletal animation because of that, unless the number of bones is very low (3 or less).

See material Examples/Instancing/ShaderBased for an example on how to write the vertex shader. Files:

VTF stands for "Vertex Texture Fetch". It is a Software Instancing technique. Unlike ShaderBased, world matrices are passed to the vertex shader through a texture. Such feature has only been supported since Vertex Shader 3.0 and is not supported on Radeon X1xxx cards and is quite slow on GeForce 6 & 7. However it's very fast on any modern GPU (GeForce 8, 9, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700; all Radeon HD series, Intel HD 3000 and above)

The advantage of VTF over ShaderBased is that it supports a very high max number of instances per batch; even if it's skeletally animated.

Take note that you will need to set a texture_unit (preferrably the first one, for compatibility) including the shadow caster besides the texture (eg. diffuse, specular, normal maps) so that Ogre gets where to put the vertex texture.

See material Examples/Instancing/VTF for an example on how to write the vertex shader and setup the material. Files:

This is the same technique as VTF; but implemented through hardware instancing. It is probably one of the best and most flexible techniques.

The vertex shader has to be slightly different from SW VTF version. See material Examples/Instancing/HW_VTF for an example on how to write the vertex shader and setup the material. Files:

LUT is a special feature of HW VTF; which stands for Look Up Table. It has been particularly designed for drawing large animated crowds.

The technique is a trick that works by animating a limited number of instances (i.e. 16 animations) storing them in a look up table in the VTF, and then repeating these animations to all instances uniformly, giving the appearance that all instances are independently animated when seen in large crowds.

See material Examples/Instancing/HW_VTF_LUT. Files:

To enable the use of LUT, SceneManager::createInstanceManager's flags must include the flag IM_VTFBONEMATRIXLOOKUP and specify HW VTF as technique.

HW Basic is probably the fastest instancing technique[^7], but is surely more compatible than HW VTF.

The world matrix data is passed to the vertex shader using three TEXCOORDs (attribute in GLSL jargon) instead of a vertex texture. The other big difference with HW VTF, besides how data is being passed, is that HW Basic doesn't support skeletal animations at all, making it the preferred choice for rendering inanimate objects like trees, falling leaves, buildings, etc.

See material Examples/Instancing/HWBasic for an example. Files:

Some instancing techniques allow passing custom parameters to vertex shaders. For example a custom colour in an RTS game to identify player units; a single value for randomly colourizing vegetation, light parameters for rendering deferred shading's light volumes (diffuse colour, specular colour, etc)

At the time of writing only HW Basic supports passing the custom parameters. All other techniques will ignore it.[^8]

To use custom parameters, call InstanceManager::setNumCustomParams to tell the number of custom parameters the user will need. This number cannot be changed after creating the first batch (call createInstancedEntity)

Afterwards, it's just a matter of calling InstancedEntity::setCustomParam with the param you wish to send.

For HW Basic techniques, the vertex shader will receive the custom param in an extra TEXCOORD.

Multiple submeshes means different instance managers, because instancing can only be applied to the same submesh.

Nevertheless, it is actually quite easy to support multiple submeshes. The first step is to create the InstanceManager setting the subMeshIdx parameter to the number of submesh you want to use:

The second step lies in sharing the transform with one of the submeshes (which will be named 'master'; i.e. the first submesh) to improve performance and reduce RAM consumption when creating the Instanced Entities:

Note that it is perfectly possible that each InstancedEntity based on a different "submesh" uses a different material. Selecting the same material won't cause the InstanceManagers to get batched together (though the RenderQueue will try to reduce state change reduction, like with any normal Entity).

Because the transform is shared, animating the master InstancedEntity (in this example, instancedEntity[0]) will cause all other slave instances to follow the same animation.

To destroy the instanced entities, use the normal procedure:

There are two kinds of fragmentation:

Defragmented batches can dramatically improve performance:

Suppose there 50 instances per batch, and 100 batches total (which means 5000 instanced entities of the same mesh with same material), and they're all moving all the time.

Normally, Ogre first updates all instances' position, then their AABBs; and while at it, computes the AABB for each batch that encloses all of its instances.

When frustum culling, we first cull the batches, then we cull their instances[^9] (that are inside those culled batches). This is the typical hierachial culling optimization. We then upload the instances transforms to the GPU.

After moving many instances around the whole world, they will make the batch' enclosing aabb bigger and bigger. Eventually, every batch' aabb will be so large, that wherever the camera looks, all 100 batches will end up passing the frustum culling test; thus having to resort to cull all 5000 instances individually.

If you're creating static objects that won't move (i.e. trees), create them sorted by proximity. This helps both types of fragmentation:

There are cases where preventing fragmentation, for example units in an RTS game. By design, all units may end up scattering and moving from one extreme of the scene to the other after hours of gameplay; additionally, lots of units may be in an endless loop of creation and destroying, but if the loop for a certain type of unit is broken; it is possible to end up with the kind of "Deletion" Fragmentation too.

For this reason, the function InstanceManager::defragmentBatches( bool

optimizeCulling ) exists.

Using it as simple as calling the function. The sample NewInstancing shows how to do this interactively. When optimizeCulling is true, both types of fragmentation will be attempted to be fixed. When false, only the "deletion" kind of fragmentation will be fixed.

Take in mind that when optimizeCulling = true it takes significantly more time depending on the level of fragmentation and could cause framerate spikes, even stalls. Do it sparingly and profile the optimal frequency of calling.

Q: My mesh doesn't show up.

A: Verify you're using the right material, the vertex shader is set correctly, and it matches the instancing technique being used.

Q: My animation plays quite differently than when it is an Entity, or previewed in Ogre Meshy

A: Your rig animation must be using more than one weight per bone. You need to add support for it in the vertex shader, and make sure you didn't create the instance manager with the flags IM_USEONEWEIGHT or IM_FORCEONEWEIGHT.

For example, to modify the HW VTF vertex shader, you need to sample the additional matrices from the VTF:

As you can witness, a HW VTF vertex shader with 4 weights per vertex needs a lot of texture fetches. Fortunately they fit the texture cache very well; nonetheless it's something to keep watching out.

Instancing is meant for rendering large number of objects in a scene. If you plan on rendering thousands or tens of thousands of animated objects with 4 weights per vertex, don't expect it to be fast; no matter what technique you use to draw them.

Try convincing the art department to lower the animation quality or just use IM_FORCEONEWEIGHT for Ogre to do the downgrade for you. There are many plugins for popular modeling packages (3DS Max, Maya, Blender) out there that help automatizing this task.

Q: The instance doesn't show up, or when playing animations the mesh deforms very weirdly or other very visible artifacts occur

A: Your rig uses more than one weight per vertex. Either create the instance manager with the flag IM_FORCEONEWEIGHT, or modify the vertex shader to support the exact amount of weights per vertex needed (see previous questions).

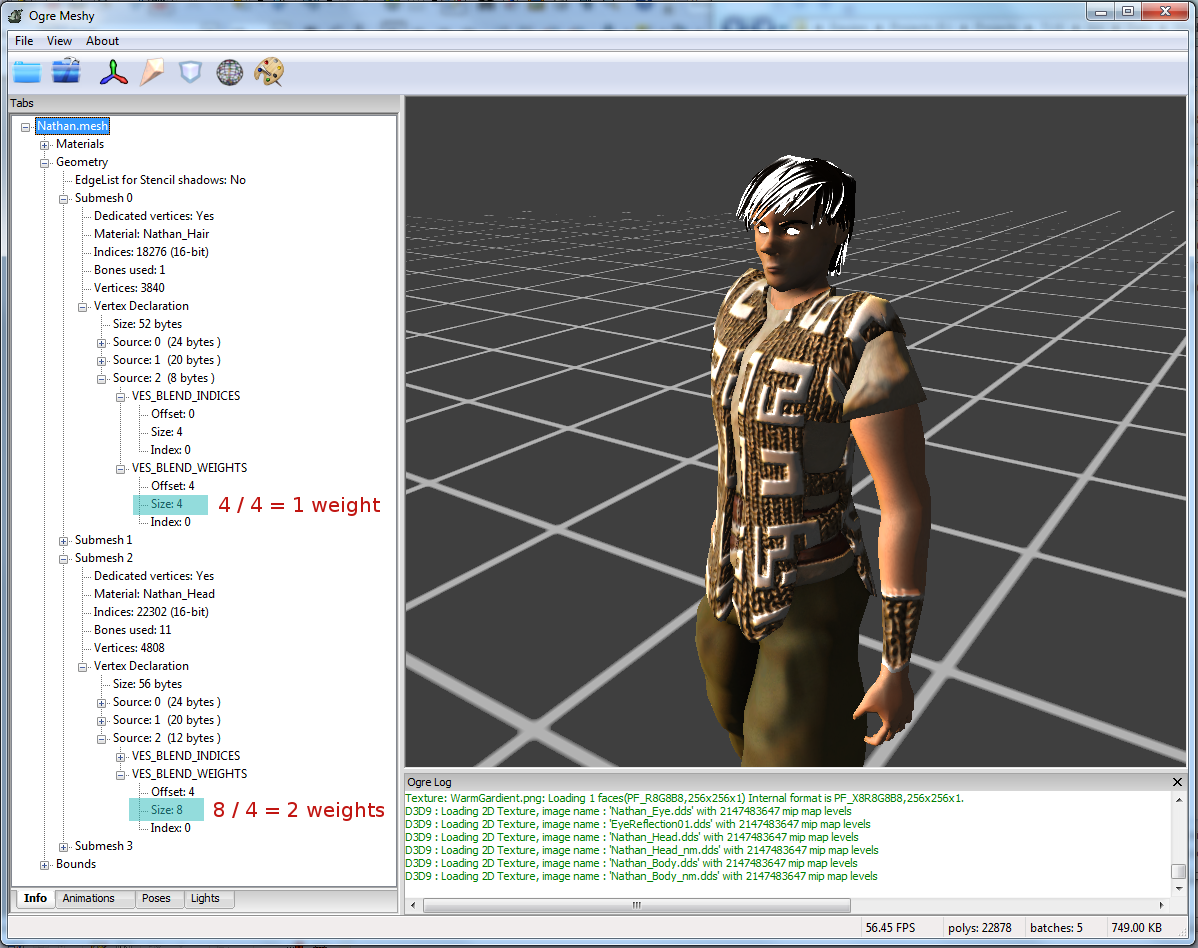

Q: How do I find how many weights per vertices is using my model?

A: The quickest way is by looking at the size of VES_BLEND_WEIGHTS and divide it by 4[^10].

In the picture above, the Ogre Meshy viewer is being used to quickly display the mesh' information. It can be seen that the Hair uses 1 weight per vertex, while the Head needs 2 weights per vertex.

[^7]: Whether it is actually faster than HW VTF depends on the GPU architecture

[^8]: In theory all other techniques could implement custom parameters but for performance reasons only HW VTF is well suited to implement it. Thought yet remains to be seen whether it should be passed to the shader through the VTF, or through additional TEXCOORDs.

[^9]: Only HW instancing techniques cull per instance. SW instancing techniques send all of their instances, zeroing matrices of those instances that are not in the scene.

[^10]: One weight is one float. One float is 4 bytes; hence number of weights * 4 is the size of the vertex element.