|

OGRE

1.12.13

Object-Oriented Graphics Rendering Engine

|

|

OGRE

1.12.13

Object-Oriented Graphics Rendering Engine

|

This tutorial is complementary to the deferred shading sample that is part of Ogre. It will reference the code quite a bit and explain some of the decisions made when implementing the deferred shading framework for the demo.

Deferred shading is an alternative approach to rendering 3d scenes. The classic rendering approach involves rendering each object and applying lighting passes to it. So, if an ogre head is affected by 6 lights, it will be rendered 6 times, once for each light, in order to accumulate the affection of each light. Deferred shading takes another approach : In the beginning, all of the objects render their "lighting related info" to a texture, often called the G-Buffer. This means their colours, normals, depths and any other info that might be relevant to calculating their final colour. Afterwards, the lights in the scene are rendered as geometry (sphere for point light, cone for spotlight and full screen quad for directional light), and they use the G-buffer to calculate the colour contribution of that light to that pixel.

See the links in Further reading to read more about it. It is recommended to understand deferred shading before reading this article, as the article focuses on implementing it in ogre, and not explaining how it works.

The main reason for using deferred shading is performance related. Classing rendering (also called forward rendering) can, in the worst case, require num_objects * num_lights batches to render a scene. Deferred shading changes that to num_objects + num_lights, which can often be a lot less. Another reason is that some new post-processing effects are easily achievable using the G-Buffer as input. If you wanted to perform these effects without deferred shading, you would've had to render the whole scene again.

There are several algorithmic drawbacks with deferred shading - transparent objects are hard to handle, anti aliasing can not be used in DX9 class hardware, additional memory consumption because of the G-Buffer. In addition to that, deferred shading is harder to implement - it overrides the entire fixed function pipeline. Pretty much everything is rendered using manual shaders - which probably means a lot of shader code.

The first part of the deferred shading pipeline involves rendering all the (non-transparent) objects of the scene to the G-Buffer. This is done using a compositor :

Things to note about this compositor :

This in an important decision in deferred shading, as it has performance and visual implications.

Also, the entire pipeline has to be coordinated with this format - all the writing shaders have to write the same data to the same places, and all the reading shaders (for lighting later) have to be synchronized with it.

We chose two PF_FLOAT16_RGBA textures. The first one will contain the colour in RGB, specular intensity in A.

The second one will contain the view-space-normal in RGB (we keep all 3 coordinates) and the (linear) depth in A.

See the references for other possibilities.

The only indicator that ogre has when rendering the scene is that the material scheme is different. Material schemes in ogre allow materials to specify different rendering techniques for different scenarios. In this case, we would like to output the lighting related information instead of the lighting calculation result.

Materials that have a technique associated with the GBuffer scheme will render using that, but we don't want to modify the materials of all the objects in our art pipeline to use them in deferred shading.

The solution is to use scheme listeners! The material manager has a method for registering listeners when objects don't have a technique defined for the current scheme: Ogre::MaterialManager::addListener().

The listener has a callback method that gets called whenever an object is about to be rendered without a matching technique: Ogre::MaterialManager::Listener::handleSchemeNotFound().

We will implement such a listener for the GBuffer scheme. It is GBufferSchemeHandler from the demo. The GBufferSchemeHandlers works like this :

For each pass in the technique that would have been used normally, the GBufferSchemeHandler::inspectPass is called, inspects the pass, and returns the PassProperties - does this pass have a texture? a normal map? is it skinned? tranpsarent? Etc. The PassProperties (should) contain all the information required to build a GBuffer technique for an object.

After a pass has been inspected and understood, the next stage is to generate the G-Buffer-writing technique. This is done using the class GBufferMaterialGenerator. The class receives the flags of the features needed by the material, and dynamically generates the (CG) shaders and material to render an object with those properties to the G-Buffer. This greatly reduces the number of shaders that you need to manage when using deferred shading, as most of them are created on the fly. Here is an example of what they look like :

(This is for an object with a texture and a normal map)

We don't want to inspect the passes and generate the material each time an object is rendered, so we create a technique in the original material, and fill it with the auto-generated information. After copying the information from the GBuffer technique, texture references have to be updated, to use the correct textures when rendering the object. This happens in GBufferSchemeHandler::fillPass. The next time the object will be rendered, it WILL have a technique for the GBuffer scheme, so the listener won't get called.

We don't want to render transparent objects to the GBuffer, as it doesn't work properly later.

To address this, we also create a technique with a scheme called called 'NoGBuffer'. If the inspectPass decided that the object is transparent, we will not add an auto-generated pass to the 'GBuffer' technique, but instead copy the regular pass to the 'NoGBuffer' technique, to render it regularly later.

This is how GBufferSchemeHandler::handleSchemeNotFound works:

In some cases the automatic material generation will not be good enough. We want to keep the option of manually writing GBuffer materials and shaders.

How do we do this? Easily! Since GBufferSchemeHandler::handleSchemeNotFound only gets called when an object doesn't already have a GBuffer scheme, adding a 'GBuffer' technique to the material will cause it to not get passed to the listener even once.

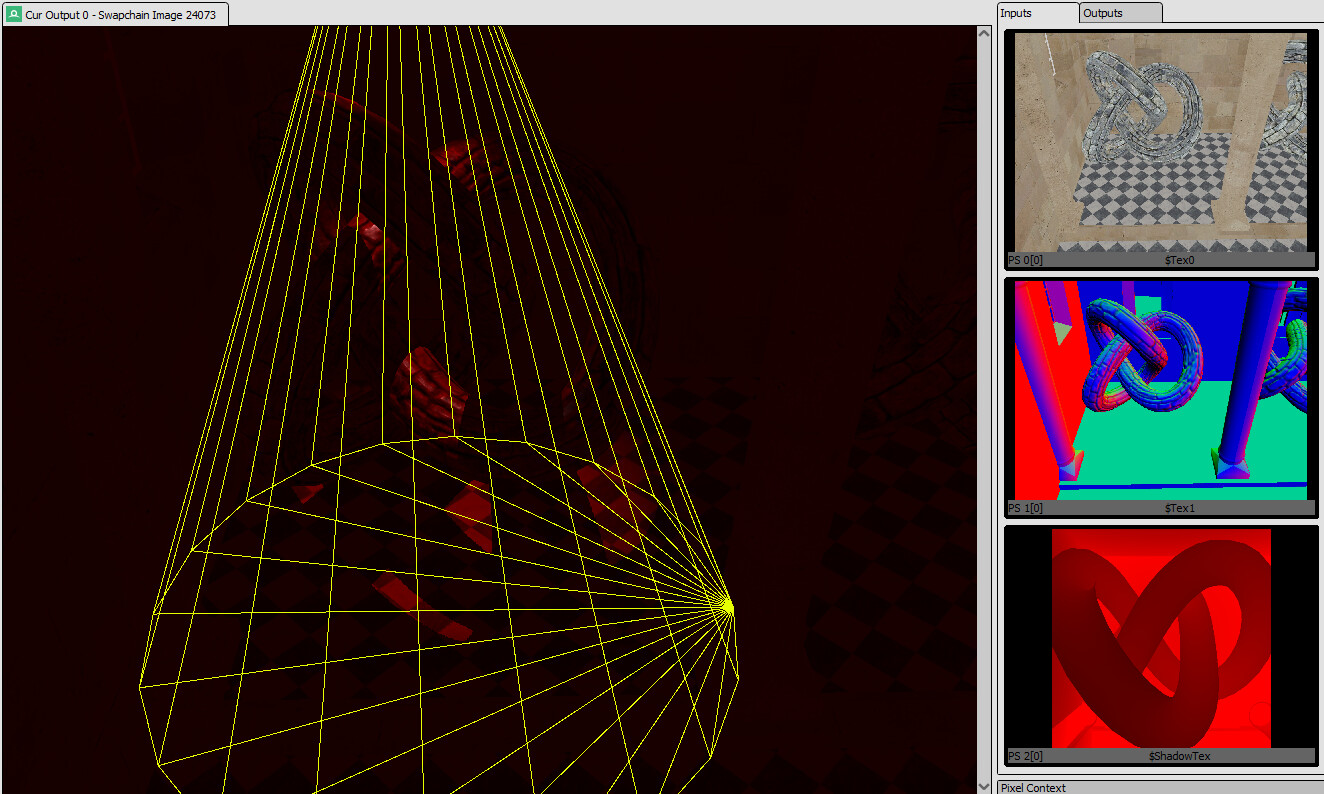

Using tools like RenderDoc, we can see the texture being built during the frame:

Note that nothing has been written to the final output yet and that two output textures are being written to (see right hand side).

In the GBuffer compositor, we built the G-Buffer for the current frame. It is now the time to use it to calculate the final lighting of the scene. This is what the compositor looks like :

Yes, it's a long one. Here is a breakdown of the compositor :

There are four target passes in this compositor.

The geometry that we want to render to calculate lighting information doesn't really fit in any classic category. It is not really a part of the scene, as the light geometry aren't objects in the world. But it is geometry (not always a quad) that needs to be rendered.

For these kind of operations, the render_custom target pass was introduced into Ogre. It is possible to register custom (named) composition passes that will be performed in the compositor. In this case, it is 'DeferredLight'. The composition pass will receive a call each frame telling it 'it's your turn, do your thing'. The class in the demo is DeferredLightCP.

The registration of the custom composition pass has to be done once, using Ogre::CompositorManager::registerCustomCompositionPass().

CustomCompositionPass is essentially just a factory for RenderSystemOperations, which are the operations that get executed during a compositor chain. This is the single API call: Ogre::CustomCompositionPass::createOperation().

So, now we get called exactly when we want, after the G-Buffer has been built and the (early) skies have been rendered. What will we do?

Since we rendered the original scene to a different RTT, the depth buffer won't necessarily get reused for the output target, so we need to rebuild it so that future objects (lights and non-g-buffer objects) will be able to interact with the depth naturally.

Also, we need to apply the ambient light to the scene. For the purpose of the demo, the ambient light is not a separate colour channel, just the object's original textures applied with the scene's global ambient light factor. In theory, you could set up a different G-Buffer to allow more flexibility, but we didn't do that.

These two actions happen in a single full-screen quad render, that comes from the AmbientLight class.

The most important stage is the light geometry. The code scans the original scene's lights, builds a matching DLight (deferred light) instance for each light in the scene, and renders away using the G-Buffer.

These lights use pretty sophisticated shaders, since they perform the lighting calculations of the fixed function pipeline themselves, and have to account for many options (specularity, attenuation, different light types and shadows, which will get talked about soon). In contrast to the G-Buffer building stage, the shaders here do not get generated on the fly. There is one big shader (sometimes referred to as an Uber-Shader) with many preprocessor options that account for all the options. (See LightMaterial_ps.cg) Note that the shaders have to be synchronized with the G-Buffer layout. A change in the layout would need a parallel change in the deferred lighting shaders.

The material generator for this section (LightMaterialGenerator class) just scans the flags of input and generates the correct preprocessor defines for the uber-shader. Some people prefer to use this approach for the G-Buffer stage as well, but I wanted to show both options in the demo.

In order to dispatch render operations manually, the following call exists in SceneManager: Ogre::SceneManager::_injectRenderWithPass().

When rendering a light, we pass the light we are rendering as the manual light list in order to have the auto params for that light available in the shader.

The 'classic' approach to rendering texture shadows is to prepare all of them before the scene rendering starts, and then apply them to the rendered objects using shadow receiver passes or integrated shaders. The downside of this approach is that you need to allocate a texture per-light (5 shadow casting lights -> 5 shadow textures) and that if you don't integrate it in your shaders you also contribute even more passes to the scene.

One of the advantages of deferred shading is that we render the lights completely, and one by one. So, we can generate the shadow texture for a light just before the light's geometry is rendered, allowing us to reuse the same texture for as many lights as we want. (We still have an overhead of rendering the scene from the light's perspective per-light).

The API call that prepares shadow textures on demand is Ogre::SceneManager::prepareShadowTextures(). The lightList parameter allows specification of which lights to prepare shadow textures for.

Important note - RenderSystemOperations get executed in the middle of scene rendering. This means that there is an active render target being rendered to. In order to render the shadow texture we need to be able to pause rendering mid frame, render the shadow texture, and resume rendering immediately afterwards. For this, SceneManager has two methods that do just that Ogre::SceneManager::_pauseRendering() and Ogre::SceneManager::_resumeRendering(), so the prepareShadowTextures call has to be inside this.

The demo currently supports just spotlight shadow casting (since it is the cheapest to implement) but the other options can be supported as well.

Here is a screenshot from RenderDoc of the draw call that renders a spotlight that casts shadows. See the two G-Buffer textures and one shadow texture on the right:

After all the lights are rendered, the scene is fully lit!

The compositor framework used to be a post processing framework, but as this article shows - it is now a 'custom render pipeline' framework, allowing different rendering approaches. However, it can still be used to post process the scene, even under deferred rendering.

'Screen Space Ambient Occlusion' is a global illumination technique that adds a bit of realism to the scene, where classic lighting often fails. However, it requires the normals and depths of the scene in order to calculate its contribution. Normally, the SSAO compositor would have a render_scene directive that does that.

However, with deferred shading, we already have that information from the G-Buffer stage, so we just need to access it!

This is what the compositor looks like :

Some notes :

The framework that this demo uses was designed to be pluggable into other projects. Some of the design considerations that contribute to that are :

The framework created for a demo fits the plugin architecture pretty well. The GBufferSchemeHandler and DeferredLightCompositionPass classes could be instantiated once on plugin setup and registered with ogre's systems. This is not the case currently just to keep the SDK build simpler.

So, the steps are :

And thats it! In the demo, the DeferredShading class takes care of that.

The deferred shading framework in the demo was designed to be usable in real applications. Where would one want to modify it ?

Indeed, it means that the framework is not 100% plug and play. But, if understood correctly, it can be adapted to real life scenarios with relative ease.

Post processing compositors that rely on certain aspects of the scene (like SSAO does) are now much easier to create and integrate with the earlier processes. An example could be edge-based anti aliasing, to address the lack of anti aliasing in DX9-based deferred shading systems.

In addition to that, the deferred shading implementation was focused on simplicity. There are many optimization options and most of them were not done, mainly to keep the demo as simple and understandable as possible.

Deferred Shading is an advanced rendering technique, that brings a pretty big implementation challenge along with it. This article, along with the demo, shows that it is possible to implement without relying on hacks and bypassing ogre's systems. Yes, it involves more advanced usage of ogre's APIs and requires a bit of knowledge about what happens behind the scenes, but is in no way impossible.